One of the most celebrated contemporary landscape artists of the twentieth century, Doris McCarthy represented Canada from coast to coast to coast. In our latest artist feature, learn about her remarkable body of work and her paintings in Glenbow’s collection.

Though she was born in Calgary, Doris McCarthy (1910–2010) grew up in Toronto, where her family settled in 1913 after years of travelling to accommodate her father’s engineering work. Art historian John Hatch has argued that “The first three years of McCarthy’s life left her with an indelible urge to keep moving, both mentally and physically. Everyone she met recognized her energy and insatiable desire to travel.”[1] Travelling would become pivotal to her art career, which began when she won a scholarship to study at the Ontario College of Art (OCA) in 1926. Arthur Lismer, one of the original members of the Group of Seven, was one of her instructors, and she soon became interested in how the Group was changing landscape art in Canada.

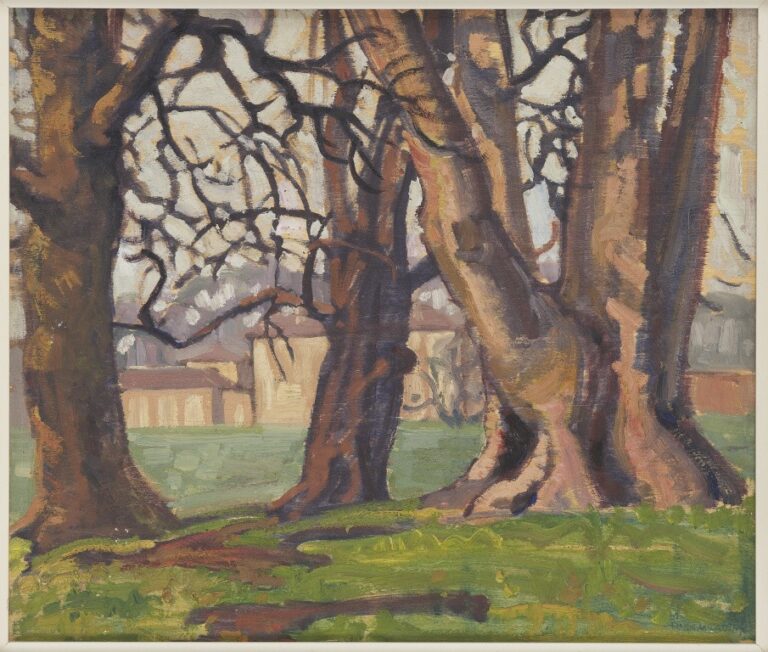

Shortly after graduating from the OCA, McCarthy began working at Central Technical School in Toronto, where the art director regularly hired practicing artists to fill teaching positions. McCarthy received her teaching certificate in 1933, but she remained committed to her painting, going on sketching trips to seek inspiration and submitting her work to exhibitions. In 1935, she decided she wanted to study art abroad and took a leave of absence to go to England. Trees in the Field, 1936, dates to her year there and demonstrates the energy and bold style she was developing. The tree trunks appear as massive, enormous sculptures, with their dramatic organic forms contrasting with the modest buildings in the background.

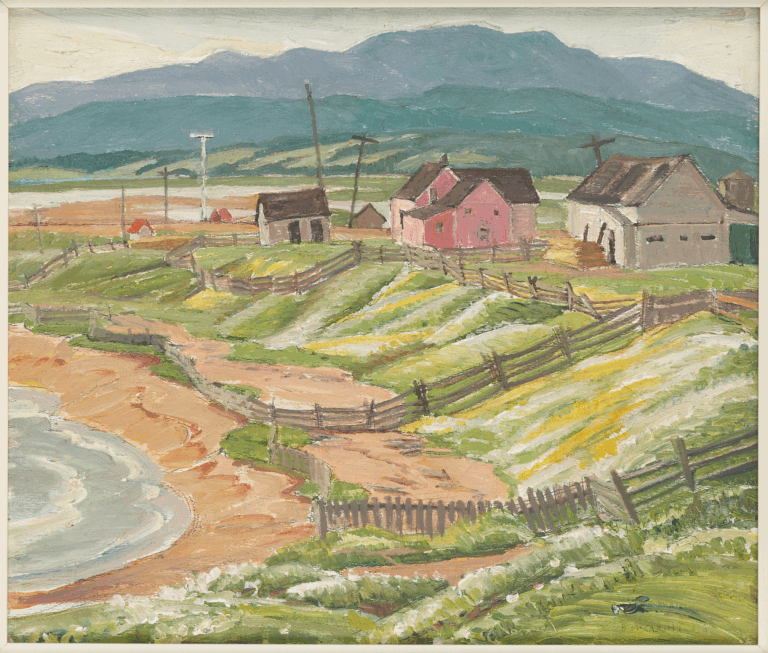

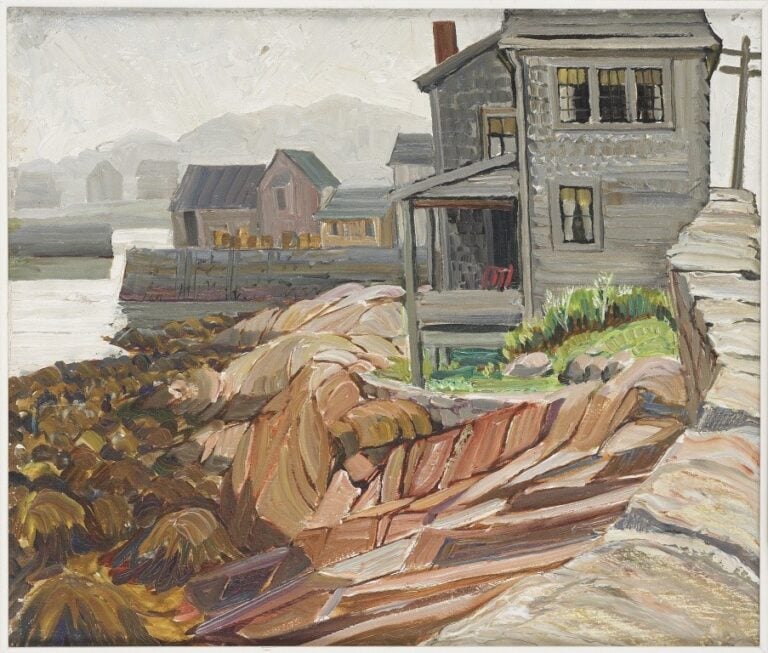

When McCarthy returned to Canada, she resumed teaching and making trips to paint in different parts of the country whenever possible. One place she visited regularly was the Gaspé Peninsula in Quebec. One of her most memorable trips was in 1944, in the middle of the Second World War. Travelling was difficult at the time, but McCarthy felt that she was “hungry for the Gaspé,” and decided to visit anyway.[2] The first day she and her friend went out painting, they were arrested by the military police as spies and held at the regional military headquarters until it could be confirmed they had permission to sketch. The Pink House, Barachois Gaspé, 1944, was painted shortly after. It captures a home in Barachois, a fishing village she visited many times; she also painted another view of buildings by the water on the back (also known as the verso) of this work.

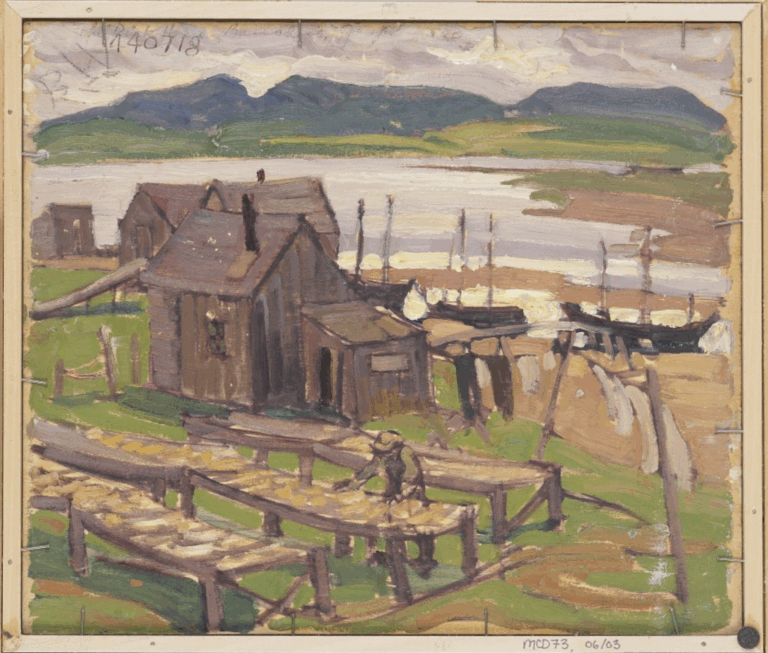

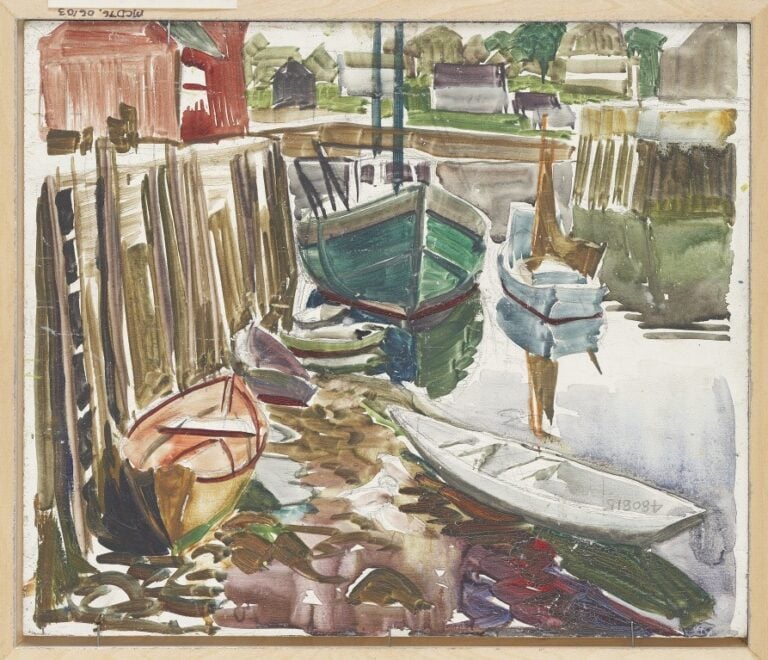

McCarthy returned to the Gaspé many times and felt she had learned important lessons from her experience there. In one of her memoirs, she reflected, “It was on the Gaspé coast that I began the analysis of form that has stood me in good stead ever since. Drawing the changing ribs of a boat, both the ones I could see and the ones that were hidden, gave me a trustworthy contour of hull and gunwale. I learned the lesson that I drilled into my students from then on, that the relationships must be understood before they can be drawn, that form follows function and what you don’t see is as important as what you do.”[3] The vigorous strength in depicting forms, as can be seen in the boats and houses in Coastal Village, 1948, was something McCarthy would bring to many different paintings—she created many works dominated by dramatic angles and curves.

As a mature artist, McCarthy travelled all over the world and across Canada. In 1972, she visited the Arctic. Having recently retired from Central Technical School, she decided to go to Resolute Bay (Nunavut) and Pond Inlet. She was deeply moved by what she saw: in describing her experiences, she noted, “I met my very first iceberg and I went crazy about icebergs and I started doing ice form fantasies,” and “Pressure ice is an endless delight. Every time the tide comes in, the sea ice is pushed up. Sometimes it cracks and breaks into pieces. Huge cakes of ice are left on edge and frozen into position. The tide as it goes out lets some of these broken floes sag against each other and freeze together in jagged clusters, with fresh snow drifting about them in scarves. All along the shore is a tumult of ice forms, an invitation to creative design.”[4] McCarthy created numerous painted sketches during her visit that became the starting point for her Iceberg Fantasy series. Building on this trip as well as subsequent visits, she completed over sixty paintings, including Iceberg Fantasy No. 21, 1974. As the title implies, these were imagined scenes, but they were closely based on her encounters with icebergs; for example, she was fascinated by their depth below the surface of the water, as can be seen below.

After a career that stretched well into her nineties, McCarthy died at age 100. She left a remarkable legacy as a teacher, with students who became some of the leading artists in Ontario, and as an artist, with paintings that reflected a passionate commitment to developing personal excellence in landscape. From her first paintings at an institution dominated by the Group of Seven to her later works inspired by remote destinations in the North, her art encompasses several chapters of the history of landscape in Canada. In its ambition and longevity, her work invites us to reflect on the possibilities for landscape in the future.

References

[1] John G. Hatch, Doris McCarthy: Life & Work (Toronto: Art Canada Institute, 2024).

[2] Doris McCarthy, A Fool in Paradise: An Artist’s Early Life (Toronto: Macfarlane Walter & Ross, 1990), 239.

[3] McCarthy, A Fool in Paradise, 241.

[4] William Moore, Doris McCarthy: Feast of Incarnation (Stratford: the Gallery / Stratford, 1991), 28. Doris McCarthy, The Good Wine: An Artist Comes of Age (Toronto: Macfarlane Walter & Ross, 1991), 151.