Summer is a season for being outside, and in that spirit, we’re celebrating the art of Dorothy Knowles. Learn more about her fascination with nature in Saskatchewan and Alberta.

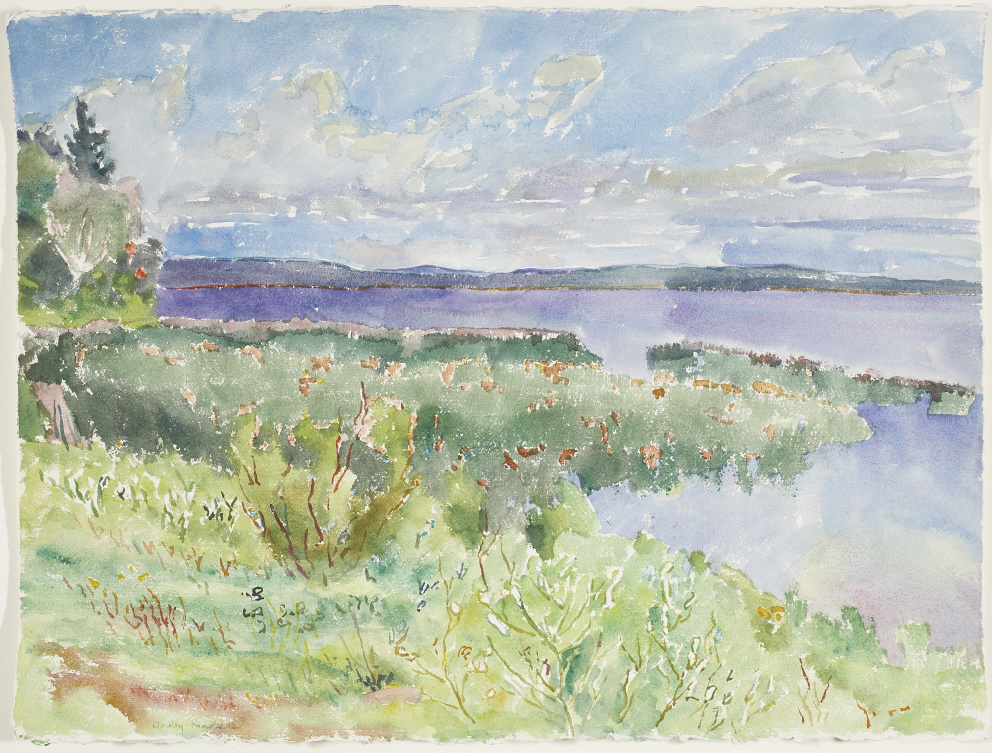

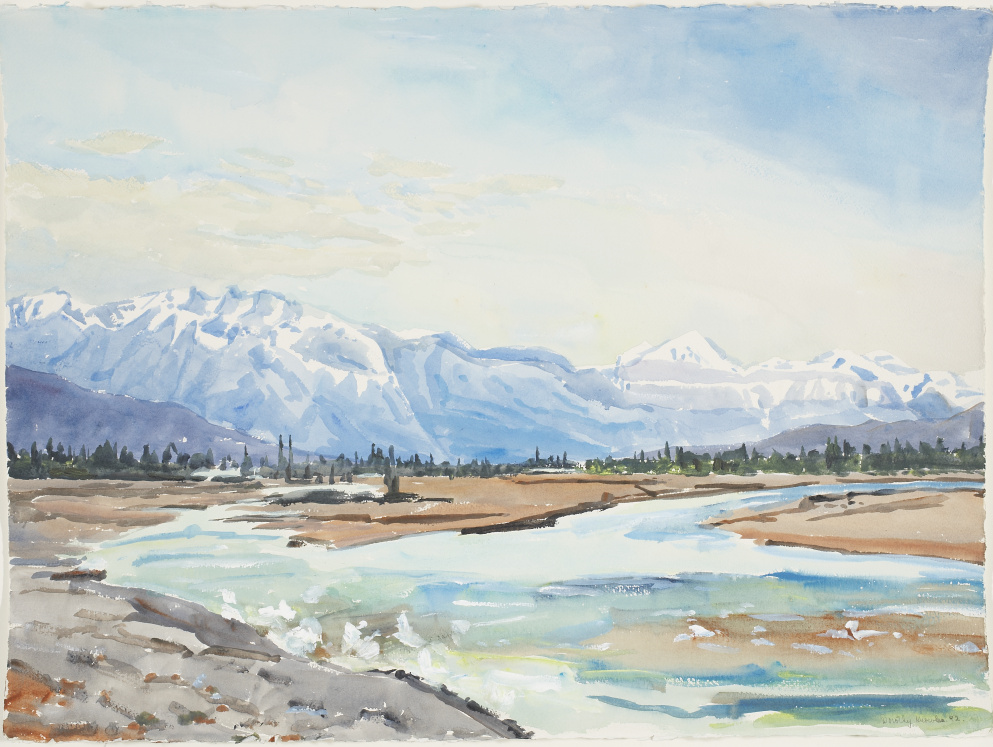

One of the most admired Canadian painters of the twentieth century, Dorothy Knowles (1927–2023) had a unique gift for capturing the beauty of summer on the Prairies. With paintings like The Narrows at Waskesiu (painted in July), Showers (also painted in July), Joe Kasahoff Cows (painted in August), and Drowned Trees (painted in July), she conveyed lush, hardy plants thriving, waters shimmering in the sun, and the air that shifts between radiating heat and cool damp in the aftermath of a summer rainstorm. She knew the Prairies intimately: she was born in Unity, Saskatchewan, and grew up on a farm, often playing outdoors by herself. As she explained, “I think that’s probably what got me interested in landscape—you know, when you’re alone you make do with what you have—and we were on the edge of a deep valley, very beautiful, about six miles across with great hills in it and gulleys.”[1] Her childhood experiences became the foundation of her art.

For over seventy years, Knowles was passionately committed to landscape painting—it was nature that inspired her to become an artist. In the spring of 1948, she completed her BA at the University of Saskatchewan. She studied biology and planned to get a job as a lab technician, but a friend suggested that over the summer they take an art course in the university program at Emma Lake. It changed Knowles’ life. She later recalled, “I learned to paint at the Emma Lake workshop. That workshop was up in the woods; I had never seen the woods, and I was so inspired by the lake and the trees—just the whole wonderful expanse of virgin forests was wonderful at that time. And I learned to paint, and I knew that was what I was supposed to do, and I’ve been painting ever since.”[2]

Knowles went on to participate in Emma Lake workshops many times, as did her husband, William Perehudoff (1918–2013). These gatherings brought together artists from across Western Canada with guest instructors from across North America, including Canadian painters Jack Shadbolt and Joseph Plaskett, American artists Will Barnet and Barnett Newman, and the legendary New York art critic Clement Greenberg. The workshops these men led inspired dozens of artists to explore new developments in contemporary painting. Emma Lake became known as space of pivotal development for abstract painters in Western Canada, among them Marion Nicoll, Roy Kiyooka, the Regina Five group, and Perehudoff, who became known for dramatic colour field paintings. Being part of this community was deeply important for Knowles, and in works such as Two Bluffs at Dusk, we can see her experimenting with abstraction. But unlike her peers, she remained focused on creating landscapes.

Landscape painting has a long history in Canada. Early European settlers created watercolours that attempted to represent places they were seeing for the first time (and sometimes, the Indigenous people they met). Painters working immediately after Confederation in 1867 depicted places across the country as a way to celebrate Canadian identity. In the 1920s, the Group of Seven and their peers developed a style of modernist landscape that some considered to be the first Canadian art movement that was distinct from European artistic traditions. As an artist, Knowles had this rich artistic legacy to draw on, but her approach was contemporary and experimental.

Like many landscape painters before her, Knowles developed a practice of working outside. But unlike previous generations of Canadian landscape painters, who relied on trains, horses, canoes, and hiking to reach their favourite places to sketch, Knowles had a car—in 1965, she bought a van that she turned into a portable studio. Using the van gave her access to places all over the Prairies, and it allowed her to paint large watercolours out in nature, instead of only making small sketches.[3] She worked outside whenever she could, and she was always interested in challenging herself to find new approaches. On some occasions, she would begin by painting a site she had selected with care, but later in the day she would turn around and paint what was immediately behind her—a scene that she had not prepared to paint at all. Other experiments included limiting the number of colours she was working with and choosing to take a specific colour as her focus.

Knowles’ Western Canadian landscapes have been shown in numerous exhibitions in private galleries and public institutions, and they have regularly received tremendous critical praise. In a catalogue for a touring exhibition in 1973, curator Karen Wilkin observed, “Colour in Knowles’ painting is always a response to particular place and light. The tonality of each painting is determined by her response to the special colours of an area, the time of day, and the season. Her prismatic orchestrations of colour leave no doubt as to what time of year it is.”[4] This ability to capture the special qualities of a season can often be seen in how Knowles represented the sky, for instance—the skies in Mountains in May, Dark Shadows on the Far Shore (painted in July), and Fall are all slightly different in tone and warmth. Similarly, just over twenty years later, curator Bruce Grenville wrote that “Knowles bathes her world in an even, overall light which gives a consistent legibility and significance to all elements [of the landscape]. It is […] the light of the Prairies, even and relentless.”[5] Her interest in light and the experience of the land would continue throughout her career.

Taken together, Knowles’ paintings not only embody her determination to represent the different seasons on the Prairies but also her fascination with exploring it. She was known to paint outdoors every summer, and she was always looking for new subjects. In her art we can see her travelling across Alberta and Saskatchewan, always finding sites that inspired her. In reflecting on her work, she claimed, “I love going to new places to paint. It’s such a treat. My favorite place to paint is a new place. I see a new place freshly. There’s a certain sparkle there that I feel, and then I think, oh boy what’s here?”[6]

References

[1] Barrie Hale, “A Vision of the Prairies,” The Gazette (Montreal), October 9, 1976, 18–19.

[2] Quoted in Shannon Boklaschuk, “The university, in a way, started my whole life in art,” University of Saskatchewan News, October 31, 2023, https://news.usask.ca/articles/people/2023/the-university-in-a-way-started-my-whole-life-in-art.php.

[3] Terry Fenton, Landmarks: The Art of Dorothy Knowles (Regina: Hagios Press, 2008), 51.

[4] Dorothy Knowles (Edmonton: Edmonton Art Gallery, 1973), ii.

[5] Bruce Grenville, Dorothy Knowles (Saskatoon: Mendel Art Gallery, 1994), 24.

[6] Elizabeth Beauchamp, “Inspiration in isolation,” Edmonton Journal, January 31, 1990, C13.