Glenbow regularly welcomes community members to visit and engage with the cultural belongings stewarded by the museum. These visits are an important part of our ongoing commitment to supporting reconnection, learning, and cultural revitalization.

Recently, Glenbow was honoured to host Iñupiaq artist and traditional tattoo practitioner Sarah Whalen-Lunn, who visited with two of her children, Bowie Whalen and Denali Whalen, and friend Mary Ann Forbes. Born in Alaska and now based in Calgary, Sarah is one of the first women in Alaska to be trained in traditional Inuit handpoke tattooing – a practice she has helped revitalize and share with communities around the world.

During her visit, Sarah sat down with us to share her journey of reconnecting with her heritage, the significance of traditional tattooing in Inuit communities, and how community continues to guide her artistic practice.

Welcome, Sarah! Tell us a bit about yourself and your artistic practice.

My name is Sarah Whalen-Lunn. My Iñupiat name is Ayaqi. My family — my mom — comes from the Unalakleet area of Alaska. I’ve spent most of my life in Anchorage, Alaska, although I’ve travelled a lot. I currently live in Calgary and have been here for about two and a half years.

I’m one of three women who were trained in traditional Inuit tattooing about ten years ago in Alaska, as part of our cultural revitalization process. That revival began years before me, led by my friend Holly Nordlum from Kotzebue, Alaska — my tattooing and laughter partner. She initiated the process about five years before I joined, and I was fortunate to be trained as part of that effort. Since then, I’ve travelled the world tattooing for our people.

I also practice other art forms — it’s probably easier to list what I don’t do than what I do! Artistic ideas come to me visually and then teach me their meaning during the process of making. I often have to learn new skills to bring those visions to life.

What first drew you to traditional Inuit tattooing?

Like many others, I grew up fairly disconnected from my culture — even in Anchorage, which we call the biggest village in Alaska because everyone ends up there. My mom was taken from her village very young. Her father was a Bureau of Indian Affairs teacher and moved her to Anchorage.

Growing up, I didn’t know we had tattoos in our culture. I had no family photos or stories about it. I met Holly while bartending and raising my kids as a single mom. She shared her vision of reviving traditional tattooing, and it blew my mind that we had this practice and lost it. I followed her work closely. Eventually, I applied through the Anchorage Museum for formal training.

I’ve always been interested in tattooing. Reconnecting to my roots became important as my kids grew up — I wanted to offer something back, not just take. Being part of this tradition allows me to do that and helps me and my children understand who we are. It also allows us to return to villages not just as visitors, but as contributors.

What does tattooing mean to Inuit communities today?

It’s hard to speak for everyone because each person’s story is unique. But at the core, I think we’re all seeking reconnection — to show pride in who we are and where we come from. In Alaska, so many people now have tattoos that we see each other everywhere. It builds visual community and pride. It’s a declaration: “Yes, this is who I am.” And we continue to carry our strength and traditions forward. But again, everyone’s journey with tattooing is personal and different.

What made you want to visit the museum today?

I’ve been apprenticing Bowie since he was 14, but this was his and Denali’s first time visiting a museum collection. It’s always a heavy experience — there’s grief and tears, but also deep importance. For me, visiting is a way to acquaint myself with Alberta, since I’m still new here. It’s like saying hello to the ancestors held in this place. It’s an act of care and connection.

What resonated with you in the collections today?

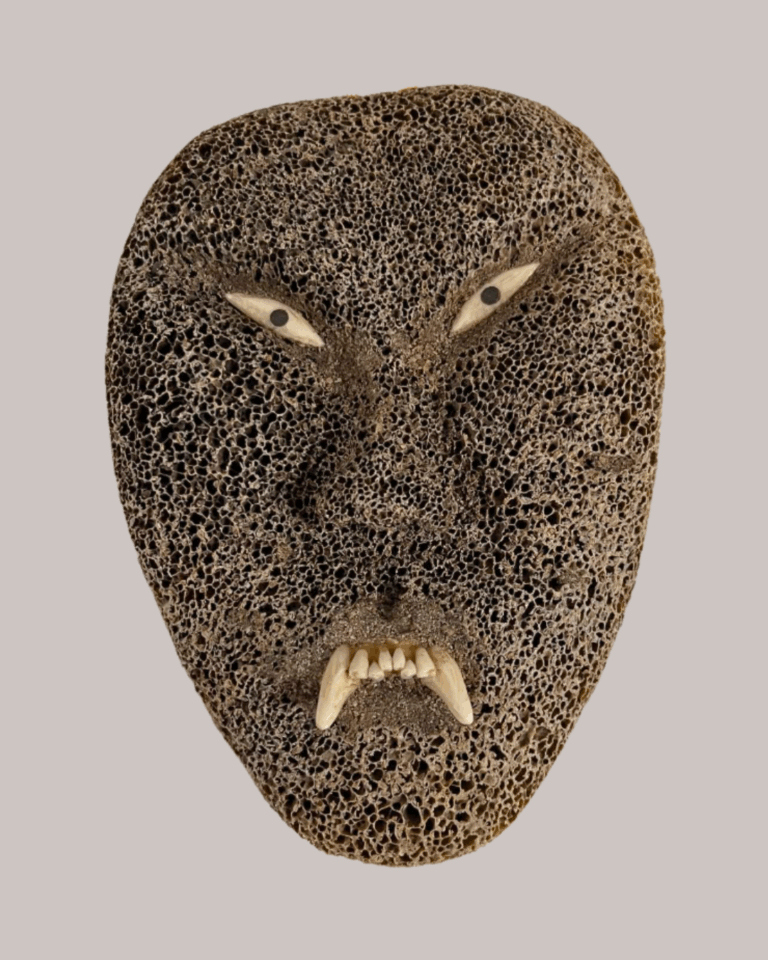

That’s a big question — I’m a total nerd, so everything! Everything from sinew and buttons to caribou and baskets. But if I had to pick: the doll with the intestine parka [above left] really stood out. Also, the whale vertebrae masks [above right] — that felt like home. You don’t see those here often. The whole experience is like taking a spiritual journey home.

Has anything you’ve seen today inspired you creatively?

Absolutely — same answer as before. Everything inspired me. I’ve been exploring what it means to be Inuk in the prairies — a foreign land for us. I’ve been using Alberta wool to needle-felt full size whale vertebrae masks, and thinking about how I can adapt local materials like elk intestine to our traditional uses. Can I make an elk intestine parka? Seeing the creativity and ingenuity of our people across time is incredibly inspiring.

What role does community play in your work as an artist?

Community is everything. I couldn’t do what I do without the support of my community. My work — whether tattooing or other forms — is rooted in the people and the land. In Alaska, we now recognize each other by our tattoos; that visual connection strengthens our community. Community allows my work to exist — it’s the foundation of it all.

What advice would you give to young Indigenous artists interested in reclaiming traditional art forms?

First, don’t listen to anyone who says you can’t do it. If it’s traditional tattooing, always prioritize health and safety. Take a bloodborne pathogens class — it’s quick and crucial. We don’t need to harm each other with poor practice. Also, go out to your communities. Talk to people, Elders, and spend time in nature. The same sources that inspired our ancestors can still inspire us. And don’t be afraid to explore. Tradition isn’t static — it’s a living, growing thing. We’re creating new traditions all the time.

You’re here with two of your children, Bowie and Denali, and your friend Mary Ann. What does it mean to share this experience with them?

It’s incredibly meaningful. There’s a question I once heard: Who do we trust with these precious traditions? Bowie and Denali — and my daughter Sandia — have grown up around traditional arts and tattooing. For them, it’s normal. They just inherently understand the importance, which is amazing. Bringing them with me and seeing their excitement is a gift. I learn from them constantly. And Mary Ann — she’s an incredible force. Being here with her means more than I can express.

What’s next for you in your work? Any upcoming projects or themes you’re exploring?

I just got back from Whitehorse, where Bowie and I were tattooing at the Cultural Centre. We’re always looking for opportunities to work in community. In my personal work, I’ve been grappling with the distance from home — trying to understand how to walk through this new land. I’m exploring how to introduce myself to this place, how to merge who I am with where I am. Much of my art now is focused on that — trying to find ways to bridge the two worlds.

Thank you, Sarah, for sharing with us!

Glenbow is committed to fostering reconnection with cultural belongings stewarded by the museum. If your community has belongings stewarded by Glenbow that you would like to visit, please contact us at collections@glenbow.org.