By Zoltan Varadi

Sexuality, gender construction and body image. Aging and mortality. Transformation. The artworks in Metamorphosis: Contemporary Canadian Portraits explore big themes, sometimes all within one piece. The exhibition is the third in a five part collaboration between Glenbow and Library and Archives Canada and draws on material from both institutions by 14 artists working in a variety of media.

Madeleine Trudeau, Acting Manager of Curatorial Services at Library and Archives Canada, and co-curator of Metamorphosis chatted with Glenbow News about the evolution of portraiture, select themes expressed within these works and the importance of this cross-institutional collaboration.

The term “metamorphosis” is applicable to what’s being expressed in any one of the individual portraits in the exhibition, but perhaps also in regards to the concept of portraiture itself. Before we get into specific works in this exhibition, could you explain how the practice of contemporary portraiture has evolved beyond the function and intent of the more historical works we’ve seen in previous installments of this series?

That’s an interesting point. In many ways, contemporary portraiture is very different from historical portraiture. In earlier times, artists had less control over what went into a portrait. Portraits were often vehicles for conveying the social stature of the sitter. They were also created as a substitute for photographs – miniature portraits, for example, originally had that function. Strong conventions informed what went into the typical portrait and it was not easy for artists to break out and do something different. At the same time, there are remarkable examples of historical portraiture which seem almost modern in their ability to reach beyond the conventions of their time: think Rembrandt’s famous self-portraits, for example. Overall, though, I think it’s generally fair to say that contemporary portrait artists enjoy a freedom that just didn’t exist during earlier times.

In the series Dueil I, Spring Hurlbut approaches human remains through an analytical lens, weighing and measuring the ashes for her father in James #1 and James #2 (above, left); in Galen #4 (above, right), she works with the ashes of her former studio assistant. Here the composition is celestial, suggesting galaxies and supernovas, pointing to the overwhelming and incomprehensible gravity of loss.

A recurring theme in this exhibition is mortality. Spring Hurlbut’s work, for example. Could you talk a bit about that? The material she worked with is certainly… unusual.

Spring Hurlbut started considering elements of mortality and death quite early in her oeuvre. This [series] is one of her earliest photographic works and it’s almost a culmination of her thinking about death and dying. In many ways it’s literal, but at the same time it’s almost ethereal. She’s [photographed] the actual remains of her father — who I think was the inspiration for the series, which is called Deuil, or “mourning” in French. When she received his ashes and was in the process of mourning and wondering what to do with them, what occurred to her as an artist is that she could actually manipulate them and through the process of grieving create a work of art.

She does so in this really interesting way. She juxtaposes elements in her work such as the scale and the ruler which are very tangible tools of measurement of the actual physicality of the body, but at the same time we’re realizing that the person is no longer there, that their soul has gone elsewhere.

She sends [the series] to the highest level with the ashes of her former assistant, Galen; she creates these almost galaxy-like starburst effects. When you see the works presented together you move from this very measured examination of a person’s physical remains to this very astral, galaxy-like swirl of ashes. It’s a very powerful work.

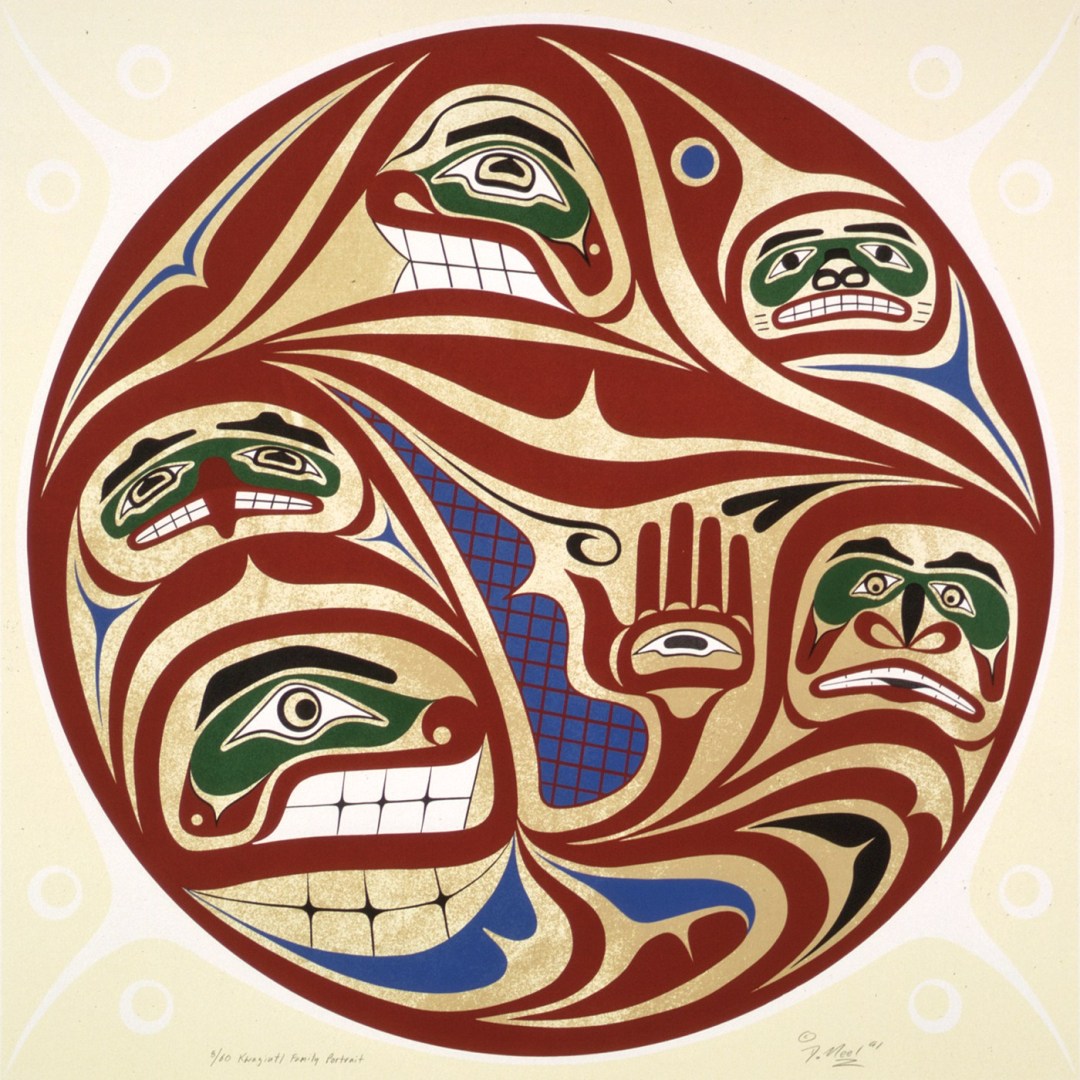

In Kwagiutl Family Portrait, artist David Neel represents his family in the tradition of his Kwakwaka’wakw heritage, portraying himself, his wife, his three sons and his artistic lineage through several generations of Kwakwaka’wakw carvers.

The exhibition also includes artists for whom transformation is part of a traditional worldview. Could you elaborate?

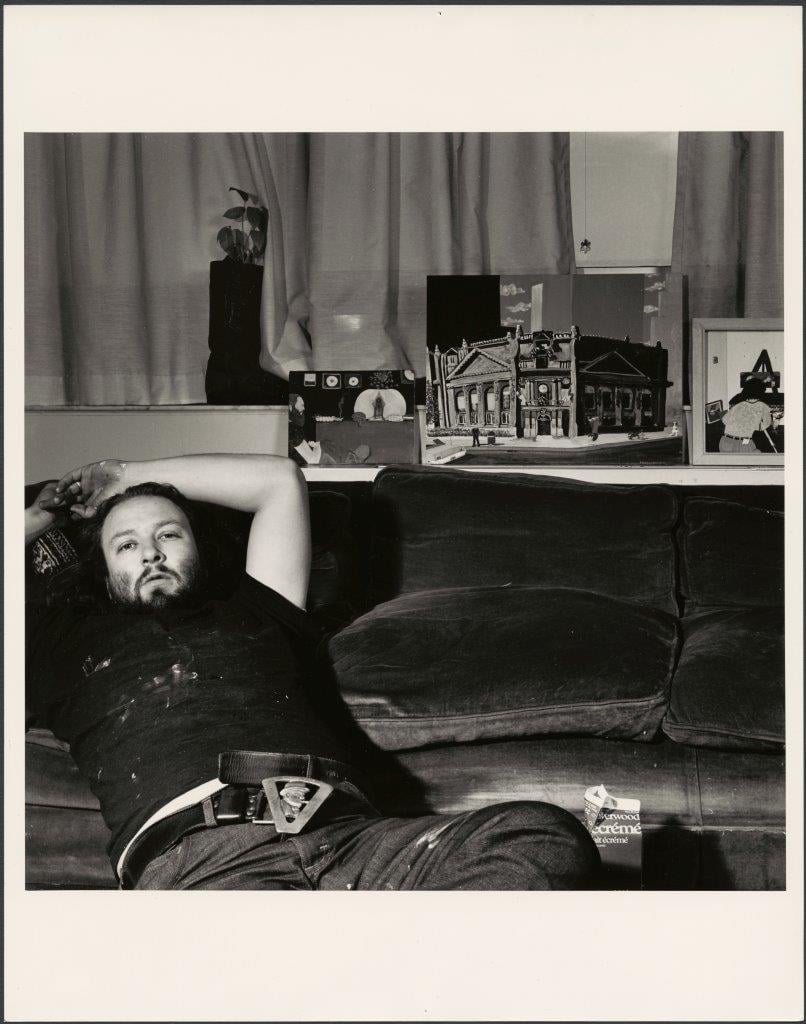

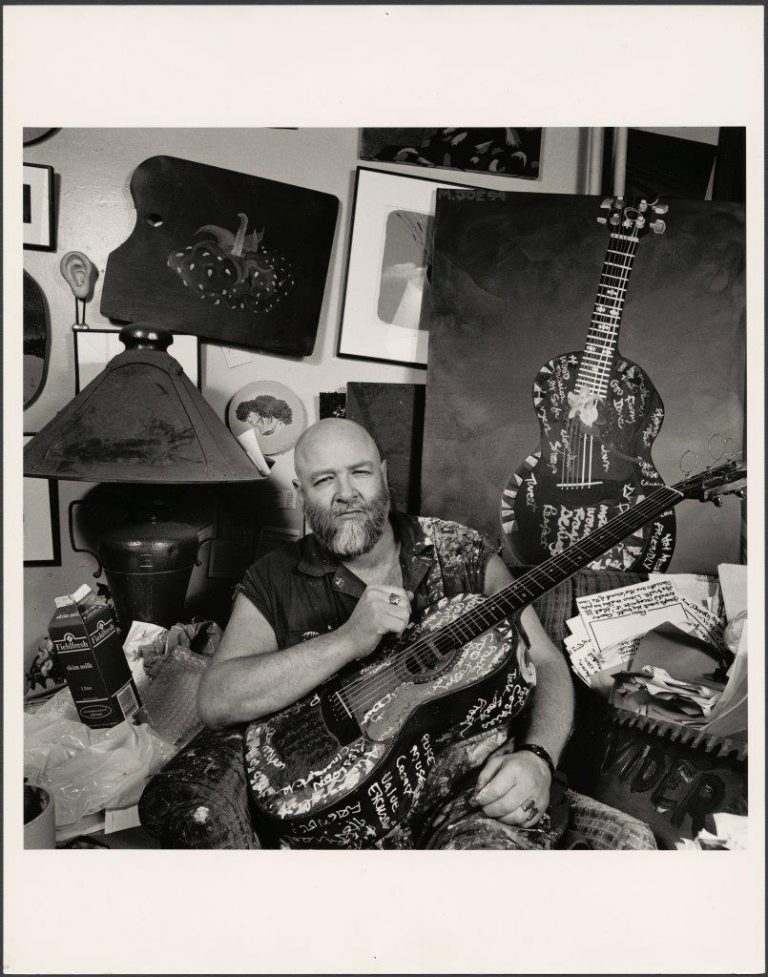

For example, the Cree artist Leo Arcand [see image at top of page], when you look at his piece, Our Future, it encapsulates the entirety of a lifespan, from birth to death, both in terms of the imagery and the items that are incorporated into the sculpture. In his worldview, this element of transformation — positive transformation — is ever present.

What are some of the other forms of transformation that are explored throughout the exhibition?

There is also ageing — considerations of how the body ages. Susan Benson’s work, for example, incorporates images of her mother and grandmother. You see family links being developed by other artists who are trying to create a larger portrait of themselves — a kind of continuity, So artists like David Neel, whose Kwagiutl Family Portrait is meant to depict his whole family genealogy in one portrait, but at the same time his intent is that everyone who looks at it will be able to see something different. He’s hoping his family’s image will lead people to see something of their own experiences in that work. There’s some really interesting explorations of time: Andrew Danson takes photographs of people in their house and 20 years later revisits them and takes a photograph again of the same people in the same place. Then there’s Sorel Cohen’s work which is so evocative and painterly — it gives you the sense of a Flemish altarpiece; she uses herself as a model and is also the creator, so she’s placing her body into different roles. She’s also exploring and pushing against traditional ideas of women in art. It’s an ongoing, multi-layered “metaphor” as she calls it.

Now that we’ve reached the halfway mark in this collaboration between Glenbow and Library and Archives Canada how are you feeling about the project? Why is it important?

These portraits belong to all Canadians and it’s very important that they be accessible to all of us, in all parts of our country. That’s why this opportunity to present a selection of Library and Archives Canada portraits at Glenbow has been so important.