On his first encounter with the artworks and artifacts in The Arctic: Real and Imagined Views from the Nineteenth Century, James Kuptana, an Indigenization Strategy Specialist at Bow Valley College who worked on the exhibition as a guest cultural consultant, says he “immediately thought of both sides of my family.”

The exhibition examines the Northern iconography created by art works depicting expeditions undertaken by the British Navy during their expansion into the Canadian Arctic in the 19th Century. It also includes Indigenous and European artifacts to provide a sense of reality to the world depicted in the largely romanticized artworks. Kuptana, along with Sophia Lebessis, owner of Transformation Fine Art, provided an Inuit and Inuvialuk perspective on its content and themes.

“My mother is Inuvialuk and father is of Irish descent,” Kuptana explains. “Some of the prints that [curator Travis Lutley] first showed me were of my traditional territory, Banks Island in the Inuvialut settlement region. One of the expeditions that searched for Franklin landed on the north end of Banks Island; my mother’s home community is on the southern tip in Sachs Harbour.”

Remarkably, given the recurring theme of naval misfortune in the exhibition The Arctic, Kuptana’s own paternal grandparents were involved in a latter day hunt for one of the ships lost in during the 19th century British quest for Arctic expansion. In 1973, Kuptana’s grandfather, Ray Creery, a retired Navy captain, was asked by Stuart Hodgson, then Commissioner of the Northwest Territories, to take part in an unofficial probe. (“Granddad and Stu were neighbours in Yellowknife for six years,” explains James.)The expedition consisted of Hodgson and his wife Pearl, Creery and his wife Pamela, and two others.

“Because my grandfather had been a navigator and had that naval background, this friend of his enlisted him and my grandmother,” explains Kuptana.

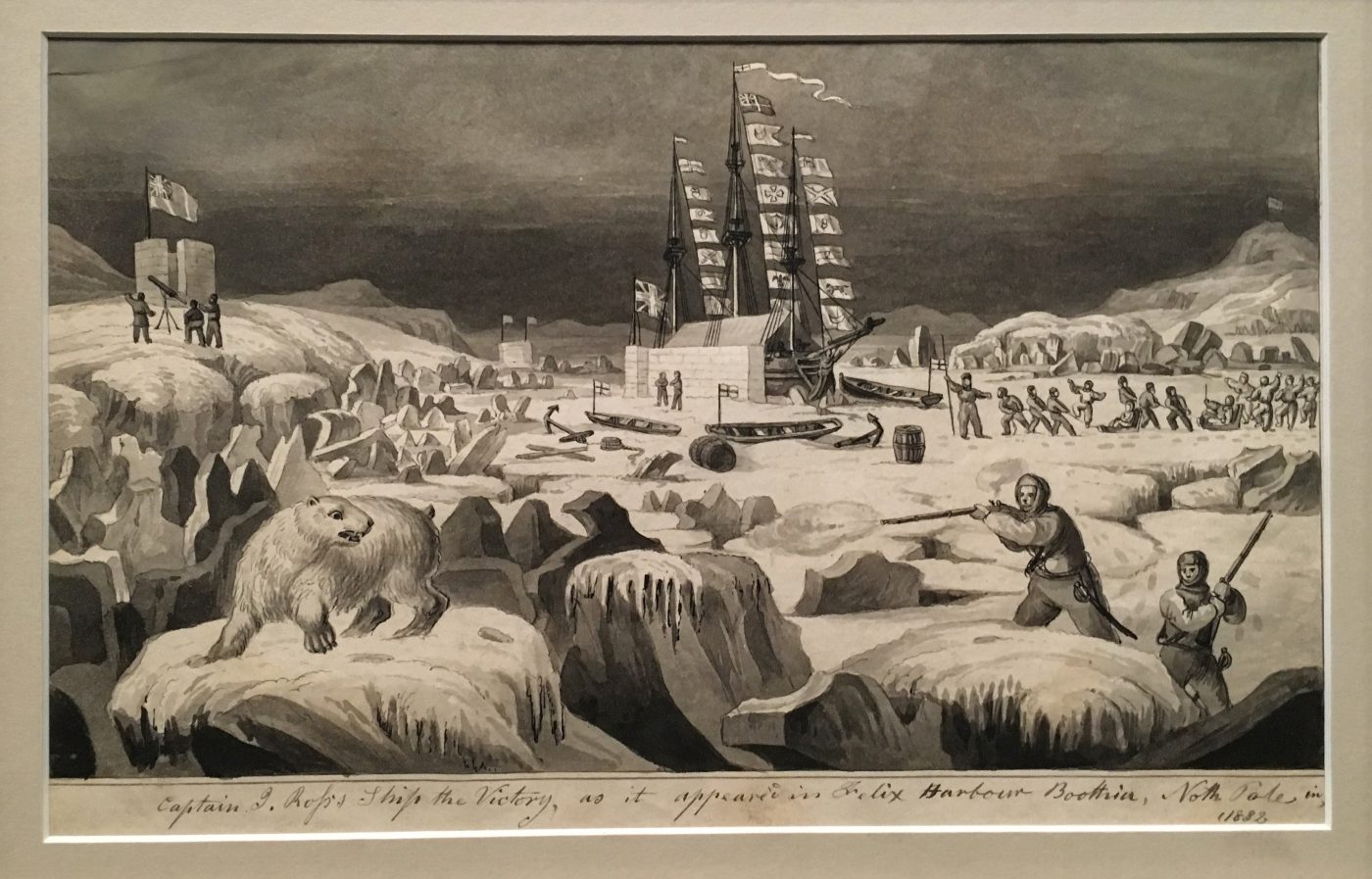

After deciding that finding Franklin’s ships, the Terror and the Erebus, was an implausible goal at that time, the group instead tried to look for the lost ship of another British explorer, Captain John Ross. In 1831, after the expedition successfully reached the Magnetic North Pole and having already endured two winters in the ice, Ross and his crew abandoned their ship, the HMS Victory, in Victoria Harbour on the Boothia Peninsula and made their way to Baffin Island, where they were eventually rescued by whalers.

Kuptana says that idea behind his grandfather’s expedition was to “see if they could add to the knowledge about the disappearance of Franklin and his two ships by seeing if they could locate the Victory.”

The team spent four nights in frame tents on the peninsula, dragging the harbour by day. But like so many before them, the mission ultimately didn’t locate anything of consequence other than some bits of timber and rope. According to Kuptana, one of the more memorable events of the expedition came in the form of a somewhat close encounter with a polar bear.

“[They were] walking on the ice in Victoria Harbour towards the east and Granny said, ‘I think that’s a polar bear’ a half a mile away or so coming towards us. Close enough for a photograph, granddad fumbled in his rucksack for his camera. Granny said ‘you idiot we better get out of here!’ The bear lifted up on his hind legs and didn’t like what he saw and turned north and took off.”

The following year, Hodgson returned to the spot of the Victory search without the Creery’s and managed to salvage a pen and ink pot, purportedly from Captain Ross’ desk.

Unknown artist, “Captain Ross’ Ship the Victory as it Appeared in Felix Harbour Boothia, North Pole, in 1832,” n.d., Courtesy of Masters Gallery.Like so many before them, Hodgson’s and Creery’s 1973 expedition failed to shed light on one of the biggest mysteries of the Arctic, but at least they walked away from their adventure with a few good stories and without having had to endure any catastrophic hardships. The same cannot be said of the 19th Century British Navy, who lost not only Franklin and his crew to the ice, but also ships such as Ross’s aforementioned Victory and then Robert McClure’s Investigator in 1850 (ironically, the purpose of that mission was to locate Franklin; the British Admiralty officially suspended the Franklin search in 1854). Despite the massive expenditure of their resources, never mind the cost in human lives, the British never achieved their main objective, either – the first successful navigation of the Northwest Passage. Simply put, however much they flexed the considerable might of the British Empire, it was no match for the Arctic.

“I think that Franklin and those explorers came in with the perspective of, we’ll bring these big ships, we’ll bring in all this canned food, we’ll bring in our typewriters and we’ll conquer this environment,” observes Kuptana. “Whereas the Inuit and Inuvialuit tried to adapt to the environment rather than conquer it – to have that understanding of the environment: what is there and what can we use not just to survive but to thrive?”