Ric Kokotovich wants to assure his caller that any sudden popping noises that might be heard on his end of the line is not the sound of gunfire. The Alberta-born artist and filmmaker, who now makes his home in the San Sebastian area of Mérida, Mexico, explains that local festivities at this time of year tend to involve an abundant use of pyrotechnics.

“The fireworks start at noon and go until two in the morning and then they start again at 5 in the morning and go until 9am,” he laughs.

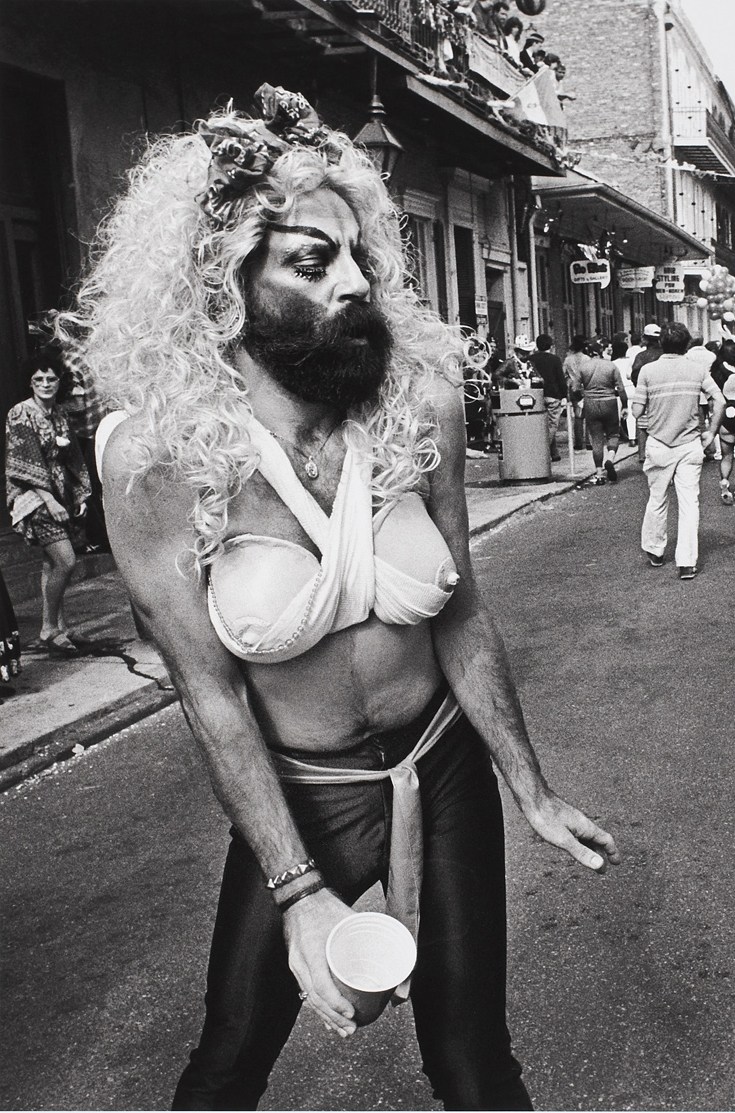

It almost seems as though Kokotovich is inextricably bound to find himself wherever there happens to be a party. Currently on exhibit at Glenbow is a body of his photographic work which he produced at the outset of his career: Ric Kokotovich: Mardi Gras 1983 – 1987. Through this series, Kokotovich’s primary objective was to create a series of portraits juxtaposing the fantastical characters of Mardi Gras against the grit of New Orlean’s French Quarter. The resultant images speak to the radical power of public procession, performance, costume and celebration in forming individual and collective notions of identity.

Kokotovich was kind enough to ring up Glenbow, in between bursts of roman candles, reminisce on his journeys to New Orleans in the 1980s.

I’m going to read a passage from the text that accompanies the exhibition: “growing up in small town Canada led artist and filmmaker Ric Kokotovich to an early fascination with what he describes as the subculture, mayhem and magic that was Mardi Gras.”

Okay, take me back to the years immediately preceding this photo series – where in small town Canada were you and what were you up to?

Small town Canada was Edmonton, Alberta [laughs]. For the rest of the world it’s a small town. That’s where I grew up and that’s where I started my interest in photography. I guess the prelude to the Mardi Gras work was… I always thought I would be a photojournalist. In December of ‘83, I told my wife that I was going with a buddy to Michoacán in Mexico to live in a village to photograph during Christmas. ‘So I won’t be here for Christmas, right?’ That’s kind of where it all started.

Mardi Gras really came out of… I woke up one day and said to my wife (again), ‘I have this idea – I’m going to photograph Mardi Gras.’ I knew nothing about it. I drove down in my car and my wife came with me because she didn’t want me to go and party on my own. I don’t know if I had it in a dream or something. Somehow the idea just came to me. The first year we didn’t have a lot of money, so the two of us slept in my little [Datsun] 280Z in the parking lot of a hotel outside of the French Quarter – it was well lit and safe.

The photographs, taken over a five year period, focus on the drag queens and members of LGBTQ community. How did you become ensconced in that world?

When we first got down there – and of course at first you know nothing – we decided to get our faces painted, be part of the crowd, learn a little bit more and just enjoy it. I had no idea what I was going to do at that point. I just wanted to photograph street stuff – that was my initial intention. I hadn’t planned to go down and meet all these wild, crazy gay guys and end up with a five-year project.

The person who painted our faces was an interesting guy who used to be head of the animation studios at Disney. He was into serious jazz and I used to be a musician, so we ended up talking about a lot of jazz. Then, he gave me some advice: If I wanted to do some real photography, rather than the tourist stuff on the street, ‘you’ve got to go there on Tuesday morning at 7:30 because all the guys start getting dressed up, etc.’ He not only gave me locations to go to that first year, he kind of said, ‘this is where the cool things happen.’ He pointed me in a direction that started it off. I didn’t really realize what I had captured until I got home that first year. There are only a couple of images from ‘83 in the body of work now. But then the next year I drove down, I went to see my friend, Bill Sorrow. He said, ‘wow, I can’t believe you’re back here.’ I told Bill I had a plan. There are all these little krewe balls that happen, which are private; as Bill was connected to the art and gay communities, he brought me inside to all of these events before Fat Tuesday happened. So I started meeting all these people who would say, ‘oh, you have to be on this corner on Tuesday at 8 o’clock because we’re going into this club no one knows about.’ It was all back door shit. That’s how it started. 1984 was the year I really focused on creating a tableaux between performers and the street.

You mentioned painting your face to become a part of the crowd – was there a process of moving away from being a fly-on-wall documentarian to becoming a part of the community?

After the first year, I never painted my face again. I was six feet tall with long hair – a black leather jacket, black jeans and a black t-shirt, and I yelled a lot. So, the guys from the first year remembered me – I ended up photographing the same individuals over a period of five years. There’s one person who’s in three of the images. You end up hugging these guys, drinking a beer with them, catching up with them at 8 o’clock in the morning on the street, dancing. They end up performing for you, and I performed for them. It was all about ‘play with me—I want you to be part of this story that I’m creating’. It wasn’t so much voyeuristic as it was interactive.

There’s certainly a very in-your-face quality to the images, a mix of celebration and defiance. You can’t help but think of the context of what that community was experiencing at that time…

Yeah, that’s when AIDS was first taking hold. Some of the guys I met… you’d go back the next year and ask, ‘where’s Christopher this year’ and everybody gets a deadpan face. AIDS was knocking the hell out of that community. And that community was made up of people from all over the United States that were down there at that time. [Mardi Gras] was a vehicle to be crazy. It was a vehicle to express all those inner emotions with the costuming and the masking. It literally was a different time. People were very expressive, and, because it was New Orleans, it was no holds barred – it didn’t matter what they did or said, how they dressed or acted.

Did you manage to keep in touch with anyone from those days?

No. I shot for five years because in year two a publisher came along and wanted to do a book, and he said you need to do five years. Well, the publisher went out of business after the third year, as small publishers often do, but I just kept going back. Then the last year I went back, 1987, I got to New Orleans and found out that my friend Bill Sorrow, who was now a very close friend, had had a fire in his house in the [French] Quarter and he had burnt his hand. While he was in the hospital getting has hand mended, he caught pneumonia and died. For some reason, that shut everything down for me. The next day I walked around with my camera, I saw people, but I literally didn’t take one image. That man had opened a lot of doors for me into that community, and when he died, a part of me did as well.

Ric Kokotovich: Mardi Gras 1983 – 1987 was on exhibition at Glenbow until September 22, 2019.

Top Image: